BY WENDY BOWMAN BUTLER

September 3, 2020

I pull up to Cruz Ortiz’s Riverside studio compound in what was once an old train station. Three separate structures box in a welding area and a fenced off yard full of freely roaming chickens and a pet rabbit sprawled out sunbathing. Metal scraps, cacti, beer cans, coffee mugs, trinkets, sculptures, and work benches splay across the driveway. The sign on the painting studio door says “Gone Fishin’” next to some wood blocks nailed into the wall spelling out “Amor.”

Cruz is always moving, painting, printing, drawing, welding. His place is vibrant with energy and color. His laughter is contagious. The building’s bones are composed of collaboration. Walls painted by neighborhood friends, photographs, and spirits of good times past living on through tacked up party posters. His space exudes camaraderie, love, and celebration while operating at an incredibly high and intense production level. His assistants are bustling around in and out of focus and he lives in the house on the compound with his wife Olivia and his children.

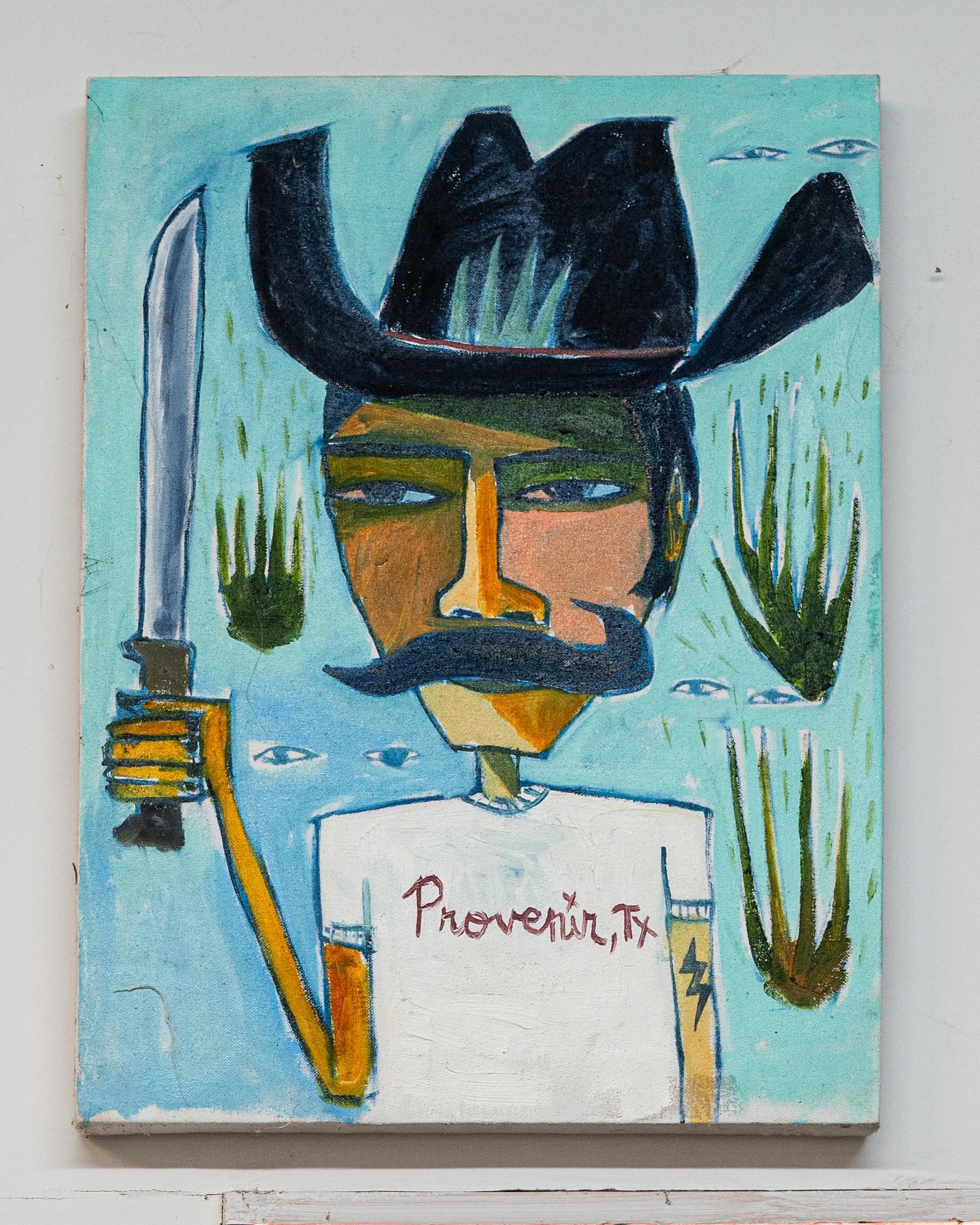

With many years of dedication, passion, and labor, Cruz’s body of work precedes him. His color-blocked, stylized technique is immediately recognizable. His branded design and political screen prints are legendary. His public sculptures—iconic. And his paintings—a mimesis of observation and dreamscapes.

WENDY BOWMAN BUTLER: All right. It’s summer.

CRUZ ORTIZ: It’s summer y’all.

WB: OK. Let’s start with something easy—when and why did you start making your work?

CO: Well, I don’t remember when I started making work. Because I really consider me making work as part of the deal when I came into the world. I remember as a small child always drawing—constantly drawing or arranging things, organizing things was always a big deal for me. So when I think of creativity and when did that start, I think it was early on, you know, a very early stage in my life. When I started to take it seriously was after high school honestly. Because in high school I wasn’t encouraged to take art classes ever. So I was in FFA like Future Farmers of America and I took welding for four years and even then my projects weren’t racks and bar-b-q pits, I was making sculpture. All the kids, the kicker kids would be like “what the hell are you doing Cruz?” I would say, “I’m making something, I don’t know.” I didn’t know at that point. It wasn’t until after high school that I really started to figure out what I wanted to do. And of course it was the punk rock community that I was also raised in. You know I’m suburbs, the American suburbs and punk rock really helped nurture my political views, my social views, cultural views, and of course the creative views of what I wanted to do. Ever since then its just been cranking that artwork out so it’s been cool.

WB: So when I see your work, I see that you kind of conceptually vacillate between macro and micro lenses—shifting your subject matter from public figures, humanity, and history to the simple and private moments of the individual. What causes those concepts to shift for you and how does it manifest technically in the work?

CO: I spent hours, you have no idea, hours and hours researching, studying, observing, and I think after I do all of that I come to this arrival at this place: well what do I want to do now that I’ve got all this info? I never know what I’m going to do. It’s probably unusual. Maybe it isn’t but I don’t like to think about that too much. I think I just need to get the work done. In fact I feel like I am never finished, ever. That’s why I have so much work I think because I am always trying to figure something out.

There are obvious different areas of my work like you said that are dealing with the intimate, historical, documentation type of work or just creating things like the plenair paintings—that’s really just observation. I am studying how light interacts with the world and how I am witness to that. I think for the most part it comes down to the witness idea—I am in the presence of this and so I want to document that.

Out of that work comes this other stuff—this realization of the importance of historical representation or cultural representation. I’m not just talking about ethnic, I’m talking about the entirety of what culture means. Of building up a society of organized efforts by humanity to present and reflect upon themselves. I think those are the bigger ideas—the huge thoughts that go into my head. All of that goes into every painting. I’m literally thinking about all of those things at the same time.

It is interesting how I do see myself when I look back especially if I go into the archive room or I dig through stuff and I notice oh my god what was I thinking? [laughs]. That’s not my problem in a sense. My issue is just get the work done. Get done what you need to get done. And you better hurry up, Cruz, because we’re running out of time!

WB: It’s interesting because this kind of ties into the next question about representation and the boundaries of reality. You explain with your own words that you “fluctuate between observations and dreaming”. It seems like you’re exploring the duality between the physical and the dream world. Do you think there is a difference between reality and non reality? And do you see your work as a bridge between the states?

CO: I think part of the drive is trying to figure that out. I am Mexican, of Mexican descent and Native American descent, and European—I’m that mix. So let’s just get that construct understood. As an artist it’s important to look into your own life and to see what makes sense. One of those things over the years that has made the most sense is that relationship of my reality and how I interact with the world, or how the world interacts with me.

As the observations become even more expanded on I think about the dream state. I think about what it means, not just being unconscious, that unconscious idea of dreaming, but I’m talking about that drive, that dream of I want this. This is something that I envision, I need to get that. I mean, do we want to get that? Those are the things going on in my head. Do I want to chase that down? Why do I need that? Is it important? Well it must be different from my reality, right? Because my reality sometimes is in complete disarray and just doesn’t make sense and there’s suffering, there’s pain, and there’s love, there’s good stuff. So then maybe I would understand my reality if I understand what I am chasing. Those are the things that I am always thinking about.

In my work you’ll see obvious observations—this is what he’s seeing, you see the painting, you see what he’s looking at, he’s interpreting that onto a surface. And then there’s other works that are just like what… was… that?!—integrating something else, maybe based on reality, definitely, probably, most likely, but now there’s this interpretation of reality and it looks like a dream. It looks like something not normal and its going deeper into how we see things on a physical tactile level. We look at things and interpret. So what you’re seeing is really the residue of that process. In fact all the work is residue. I’m cranking stuff out. I’m trying to get to something and that’s why I fluctuate between drawing, painting, today I’m welding. I just did a big ol’ painting yesterday and now I’m like ok [claps] that was cool…

WB: Switching between mediums. It’s important.

CO: Yeah yeah. I’m just fluctuating—going back and forth. It’s the only way that makes sense for me. Then I’m wood cutting, and then I’m printing 200 prints off the letterpress or arranging type or engaging in illustration or graphic design. Those are the things I’ve always fluctuated back and forth between. And it’s all just trying to make sense of what are we doing here and what are we here for. I know. It gets crazy.

WB: We were talking about discipline earlier before we started recording. How has discipline affected your success and your work?

CO: I never use the word discipline. But it’s true, it is a discipline.

WB: Well, making yourself do something. There are days where we don’t want to make work. Even though we are creative and we have things that we want to say and we have things that we want to make, there are days where I wake up and it’s hard for me to get down and do it and that’s discipline. And sometimes those days are the days that you end up making the best work.

CO: When I think about the word discipline it’s exactly that. There’s a regimen, there’s a dedication, a commitment and I don’t ever have to deal with that. I think the discipline if anything is the actual backstage production of what I’m doing right now. So that means the real stuff—the business part of what it means to be an artist. I think those are the things that I hate doing but I need that structure if I’m going to be doing the work that I really want to do. That’s where it becomes kind of nuts.

Starting off when I was younger, I was doing everything on my own and it just didn’t work. After talking to some other artists, they were like, “Cruz you need to take this seriously—this is your career.” I had people like Carmen Lomas Garza, Chuck Ramirez and a bunch of folks from different backgrounds, curators would come from all over the world to see my studio and they would say, “Wait, you’re still working a real job?” And I would say, “Well yeah, how am I going to make it?” That just didn’t ring a bell. It wasn’t until I had to make some big changes and when I met my wife Olivia, it was just [snaps] immediately like oh wow… and I had someone to help me. I think that’s really what expanded everything—meeting her. She brought an entirely different game to my game and I was able to work in a much more fluid, thoughtful production mode that was just seamless. Now we have payroll. I think about payroll [laughs]. But those things are the real things about being an artist. You have to take your work seriously. Just do your job.

WB: Absolutely. And it’s great to have a partner who uplifts you. There can be so many scenarios where you are actually with somebody who drags you down.

CO: Right totally. Getting a good team is always so good. Now I have a network of people who can help me completely. Whether it’s PR people, whether it’s large-scale fabricators, small-scale fabricators, studio assistants, interns, project managers, studio director, archivists that we hire to come in and check stuff out. There is a huge production and it becomes a lot to think about but at the same time I haven’t been this productive in my life as I am having everyone to help me. It’s been awesome.

WB: How do you think your work refers to storytelling, heritage, and history, and simultaneously how do you feel history is going to refer to your work?

CO: I’m a big fan of research. A lot of my work is research. One of the things I’ve always dug into are different artists and I really dig into what they were talking about. I think it might be because I’m in San Antonio and there are just not a lot of people I can talk to. I’m constantly writing curators and picking their brains but the best source is artist’s lives—other artist’s lives. One of the things I’ve learned is how to dig into your work in a way that is going to make sense.

WB: And be authentic.

CO: Yea, and that’s the thing—I try to understand what authenticity means and looking at all of these artists and being influenced by them. When I was starting out especially being punk rock and a screen printer, one of my biggest influences was Andy Warhol. I was just so amazed by the idea that he had a factory. Thinking wow, that’s cool—he went into production mode. Donald Judd, Jeff Koons—all of these different people went into production mode with these big production houses of making work.

I was on a trip of painting, looking at Pierre Bonnard and Matisse and their relationship and how they wrote letters to each other and I found out that Matisse had a four story building. The bottom floor was the show space, the second floor was his morning studio, and then he would go have lunch on the upstairs veranda. Then in the afternoon he would go to the third floor to the afternoon studio. He would have all the staff, with four different easels and four different still lifes, four different models, and they would rotate. He would just knock stuff out.

Rembrandt, Francis Bacon, all those folks had a method, had a production to their work. I look to those sources not in just production but the articulation of my work—trying to understand what I’m trying to do at the same time producing authentic work.

“I came to the realization that what I am doing now is going to be more important 200 years from now.”

WB: You really nailed it with how your work refers to history especially in your process. I was also asking how you think history is going to refer to your work?

CO: Understanding the arena of work that I’m dealing with where I’m thinking about history, thinking about historical referencing, that’s pretty specific in some of the work. I’ve been working on a series documenting people. It started off just painting my wife and I realized this is cool. I was doing it for my kids. I’m painting her and looking at her while painting, and I’m thinking I get it now. I understand. Alice Neel did this. In a way that I didn’t grasp just by looking at her artwork on the museum walls or in a book. But the process of me looking at that person, talking to them, there was this relationship building and I thought that’s really interesting [laughs in awe]—this is a different depth of what it means to be a portrait painter that I never knew before.

Immediately after doing those, I started inviting friends and people would come over after I would say, “Hey I really want to paint you. I find your story to be amazing.” And that shows how portraits are narratives. Looking at the portrait not just as a poetic form but really digging into the narrative part. It becomes this portrait vs. narrative. It becomes all entangled into one piece. I thought, this is historical! Wait a minute, I get it now. Understanding Velázquez in a different way, where I could really look at his paintings and think ohhh that’s interesting how he painted that pope dude to look so dead and beat and evil. [Laughs] Looking at Manet and how the brush stroke really enabled picture making vs. skipping that part and going straight to emotion right? So, those are the things I look at and think about in my history paintings.

So now I’ve been documenting people in Texas history and even Mexican-American history who have been overlooked. And right now we are going through this tremendous amazing change. When Trump got into office everything completely shifted. We went from rainbows and unicorns to a complete other side of the world that the United States hasn’t seen in a long time. He’s not a new construct. He going based on a very old construct. And he’s adapting that to now. We haven’t seen that in a while. To see him change the cultural landscape in such a quick time is pretty amazing. Not great. Just whoa, unbelievable right?

At the same time you see monuments crashing down and we're questioning history even more now. We’re looking at it and understanding it differently. We’re digging more into that and I think I’m kind of caught up into that sweep of ok well then that’s interesting and I go into research mode again—digging into the cultural past of Texas. We are really close to all the missions here in south San Antonio. I had been going and painting those missions. It’s one thing to be like “oh look at the beautiful missions—so pretty, they’re just so beautiful in the sunlight.” And I think OK well let’s talk about that. Let’s dig a little deeper. Why are there 5 missions in one area. Most missions are a day-on-a-horse apart all the way up the coast. San Antonio has 5. So you have to think—how did that happen? The ranch lands that were developed around here were just amazing. The aqueduct system was world renowned at that point. Like whoa that’s pretty cool. They did that in the middle of nowhere. So looking at that history I started documenting the missions with a different look and I’m painting them trying to find that emotion of what it means to be documenting this old empire.

So those are the things I look back on a lot as far as how am I making work now. Then I came to the realization that what I am doing now is going to be more important 200 years from now. So then I’m like, OH DAMN. Let’s not think about that. I need to eat a sandwich. Time to eat a sandwich! [Laughs] And of course I’ve gotten past that. But now even more so, I’ve been writing so much more. I have three sketch books at the same time. One where I am just documenting the days. Even painting a still life during the pandemic and it becomes even more of a presentation of highlighting this intimate relationship with a still life plant.

WB: Even the term “still life” in quarantine is just so thick with metaphor.

CO: [Laughs] Yeah, we’re freaking out about these bigger things that are also so small. It’s kind of interesting to see that fluctuation, like you were saying. Whether it’s jumping from medium to practice or modes of production to just switching on the observational focal points that I’ve been paying attention to. Whether it's politics, whether it's a landscape, whether it's a plant in the studio, whether its Olivia, whether its friends coming into the studio or I’m going to their place. Those things are all just about the work. It’s just constantly realizing there are no rules. There are no rules.

“...it’s about paying attention to your art. Paying attention to the products you are making. The residue. And letting the work behave on its own and then paying attention to how that behavior interacts with your life...”

CO: You know what’s funny. There’s only one thing I’ve been struggling with and that’s the idea of abstraction like Rothko and the school of New York type of abstraction where they rejected the image and tried to go past that and straight to the emotion. I see a lot of artists do that work and I am just always like, how did they get there so fast? Peter Doig one of the YBA artists, Young British Artists, who are older now, he was talking about it too. He said “Abstraction is a place that you arrive to.” You just don’t make pretty colors. That becomes decoration. So that’s where I keep digging my heels in the ground and I’m getting closer to that area in my work based on a maturity. Even though I am like, oh my god am I maturing this is just bizarre! I just want to go back to screen printing and punk rock posters sometimes, you know? But, it’s about paying attention to your art. Paying attention to the products you are making. The residue. And letting the work behave on its own and then paying attention to how that behavior interacts with your life and how to figure out the next step.

WB: It’s really really hard to get to that abstraction level. It’s something that I’ve never even been able to brush close to. If you look at Picasso for instance—it wasn’t until the end of his career. All of those artists.

CO: Yea Picasso didn’t arrive at abstraction until years of other works. And then once he got on that highway it was just like [sweeps hands together] took off! Even Matisse—what he was doing was one thing, but toward the end when he did that chapel, that was like reduction at its finest. Where there’s this incredible, solemn understanding of presence. Of human and nature. It was really cool to see. If you really pay attention to that work you see that happening. I love looking at it and I get it. When you go to the Twombly stuff in Houston—you see those big pieces and you get it. You understand his life living in Rome that he went straight to the source of western civilized understanding of mark making. I try to do the same thing—looking at epicenters of work. So when you go to Mexico City and those kind of mega epicenters, you think about Jeez this is centuries old of production and thought. Then you dig in deeper and think I have to go back to the studio. What am I going to do? I’ll make an oil painting. Understanding the fragility of those things is important.

WB: I’ve done a lot of introspective work on my inner child and reading about the inner artist child. Do you feel connected to that part of yourself? And if so, how do you harness and protect that from these other outside things going on?

CO: I definitely have a lot of outside things going on [laughs]. In more ways than you can imagine. Just the in-house on the ranch here in the studio there’s just so much going on with my family life, my children, and the management of the work. That’s why I tell people to hire people. Even if you get $20 on a Friday but you sold all of your work and you paid everyone, guess what? You get to make a new painting. I’m a firm believer in that—just trying to get your stuff done.

I am actually arriving at that point of understanding myself in the work. And it’s been a really long journey. Before I started off, I knew that the work that I made was a reflection of myself so I made this alter ego. It is an easy device for humans. We do that right? We can’t deal with our own shit so we make an alter ego that’s going to be a target of the vulnerability where I can guard myself. That’s exactly what Spaztek was in those early years—just damaged me. Not willing to really show my face, I made this cartoon person. Spaztek was a device made to take that hit, to take those risks, that I knew needed to get done. Spaztek had a nice run. Beautiful run. Great run. And then he shifted to The Cowboy. Then the Yanaguana Boy. Shifting characters and naming my paintings after these alter egos and then it just became just the ego. Just the presentation of that portrait of me. And then in a way those became abstracted and reduced to when I was just doing the face. Just the body and the mangled body. Like this [points to a painting] is a great example of the figure just a little off.

WB: It’s almost animalistic like how an owl can turn its head all the way around and face you.

CO: [Laughs] Yeah! Yeah it’s like thinking about that deeper understanding of colonial damage. A lot of Mexican Americans if not almost all of them don’t realize that we have deep colonial trauma. So I am reflecting on that, on my personal traumas growing up, and what that means. It’s all come to this interesting area of my work where now I am starting to say, you know what, now is the time, just draw yourself dude. Dig in deep. Kind of like the Rothko move of skipping over figuration going straight to emotion, but I can’t do that. I go right through figuration, and right through that asteroid belt.

WB: And you have to be honest to yourself too, right?

CO: Yes, and that’s what I know. So, I know figuration. That’s part of my reality is my body. The history of my body having gone through so much trauma or historical trauma. And then, you can’t get to the next step without understanding that. It’s like with anything. Like with therapy, you have to admit, or come to the arena, or the platform of yea this is the problem now let’s fix it and let’s jump in. So I think that’s exactly where I’m at right now—just understanding that it’s important to acknowledge, to engage in some sort of healing type of practice and then just channel that in. Out of all your experiences, get through that asteroid belt, get to the next nebula and then let’s engage in that. I am looking at my work in a deeper way.

WB: It’s healing.

CO: Oh its very healing. I mean the whole thing is about progression of healing into a more solid state and I think that’s what is happening with the work even more now. I say this all the time—every day I feel like I am closer to making the work that I want to make. It’s been so long. I’ve been painting forever and I’m just getting there. I don’t think I’ll ever finish.

WB: It’s a process for sure. Everything that you do. And letting out that uninhibited, curious, ambitious spirit that we’re all born with and that society kills over time is the process of anybody who’s creating anything and being true to that part of themselves.

“...just make the damn work.”

CO: Right, and I think that’s where you have to take the time. There’s definitely that discipline of making those important risk decisions and paying attention to the process of reflection and the small growth. People ask me “Do you consider yourself a Chicano artist?” And I say, “well I consider myself Chicano in a political sense but I’m obviously Mexican American.” And there’s always these ethnic conversations, people asking, “Oh what are you?”

WB: Needing lables.

CO: Yea labels. And I’m fine with that. I don’t mind it. I love that stuff. I’m obviously that.

WB: You’re literally screen printing labels.

CO: [Laughs] Yea I know people always say, “You’re actually doing that.” So I understand that too—what it means to be Texan, new Texan, and how we evolve to different understandings of society and how we see and identify ourselves. But going past that and really going back to that understanding of I’ve got to make work right now and I’ve got to preserve these small little moments. It’s about marking time. I’m on a little timeline of just cranking along.

The last five paintings have been going into this reductionist mode—even the landscapes behind you. I’ve narrowed down like five colors that I want to use and that’s it. McKay Otto was the one who told me, “Cruz you use too many colors.”

WB: That’s so interesting because when I was coming up with these questions for you and looking into your work I was thinking about how you actually have such good control over your color palette.

CO: Yeah [laughs] I feel like it’s only been in the last year that I really feel like it’s controlled now. It’s funny you say that. McKay was saying these prophetic type of observations I guess and he was just talking to me and I was just listening. I like listening to the older painters like Bill Anzalone. God that guy is a genius. He says “Oh Cruz you’re a picture maker.” And I’m like “Why do you say it like that?” And he makes me think about the beauty of going beyond the picture. Yeah it’s a picture but do you want to make pictures? Or do you want to make a painting? So those things happen all the time and the last couple of paintings have been that. They’ve been really digging in deeper. I’m understanding things differently. So now, I went into the archive room and I was like I feel like I’ve done this before. Wait I remember that painting and that’s what I want to do now! So that’s when the realization hit—the shit that goes back to the future stuff—if I don’t think and just make the work, eventually it will make sense later on. So just make the damn work, don’t think about it, just crank out the stuff.

WB: That’s what I’m titling this.

CO: [Laughs] Just crank it out. I mean there are works in there that are 10 years old and i’m like oh I get it now. I understand that now. And it’s kind of cool. So I’ve been pulling them out and hanging different stuff from when I was in that area where I want to be now. It’s kind of interesting how that happens. Now I’m looking at the archive and I’m like, get rid of this I am done.

WB: No! Don’t get rid of it!

CO: I know trust me Olivia will never let that happen.

WB: [Laughs] In the dumpster pulling out work.

CO: Oh I’ve had people totally come through my trash.

WB: That’s pretty awesome. You know you’ve made it when

CO + WB: People are digging through your dumpster.

CO: I’ve had studio visits where the recycle bin is right there and they’ll say, “But what about…” And I’m like “Don’t even think about it. That’s not for anyone to see.”

“...power never belongs to you. The power never belongs to anyone. It’s supposed to be available for everyone.”

WB: How do you define power? And when do you feel the most powerful? And I mean that in the sense of when do you feel the most filled with power? You know what I mean? That flow state.

CO: Power is very interesting. Obviously when we think of power, we think of, well I think of the abuse of power. And power is kind of like abstraction—it’s an arrival to. You’re not just born with power. Correct power is nurtured into. You’re nurtured into that realm, then once you have the power then you know what to do with it in a wholesome way. I think if that’s the case, then all these paintings are power. These are powerful things. It’s taken years to get to this point. If I think about the paintings, and understanding what I was saying earlier about making work and letting the work behave on its own, then that means the power never belongs to you. The power never belongs to anyone. It’s supposed to be available for everyone. When I think about power, I don’t ever want to say I have power, because that just seems so stupid. [Laughs] Power is something to be distributed—it’s something to be enjoyed. It’s that feeling when my wife has the kids in her arms—that’s power. That’s a powerful thing.

I think in our society we misunderstand completely what power means. We think of firearms as power. Well that’s not power at all, that’s the complete opposite—it’s fear. Those are things that are sure signs of people who weren’t nurtured correctly in a humanistic way or with dignity. Obviously we live in a screwed up world so you can’t expect that all the time to happen. We can try. I was a teacher for so many years and that was the whole point was to nurture children so that maybe there’s a chance for their generation, if I nurture and invest enough time, I can actually help later down the line.

And going back to the future right. I need you to understand you will get there but once you get power what are you going to do with it? Look behind you and share it. Give it to someone else younger than you. Bring them along. This is what you do. This momentum this infinity type of thing where it’s not linear at all, it’s supposed to rotate. I remember one of my professors said during a drawing exercise outside and he says, “I need everyone to draw this tree” [laughs] it was funny he goes, “I don’t want you to draw the tree, I want you to draw the energy of the tree.” So we’re all like “All right whatever, whatever!” You know we all probably smoked too many cloves.

WB: [Laughs]

CO: So ridiculous. [Laughs] Anyway, we were drawing and he’s like “Look at that tree. Everything in nature is shifting slowly.” And I was like “Holy moly!” I looked at trees differently and thought “He’s right.”

WB: And they’re so connected too.

CO: Through the air and they talk to each other and now I look at trees and think all trees are turning. What you’re seeing is a big slow gradual turn. The leaves turn out and open and wilt and rotate. That’s power—to look at something like a tree and appreciate that kind of power and document it and share it. I think about that stuff all the time. Even the teacher thing. Teachers are the most amazing creatures right? Because they understand power more than anything. They’re nurturing that and the work that they do is not obvious the next day. It’s 20 years later. So it’s the same thing—you paint for the future. And you know, hopefully that works out.

WB: Damn, well I think that was a pretty good place to end it. Thank you so much!

CO: Yeah no problem. This was awesome!

WB: This was so great.